Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products - Nir Eyal

— books, product & design — 55 min read

About the book

- Buy on Amazon

- Goodreads reviews

- Pages: 256

Personal Summary

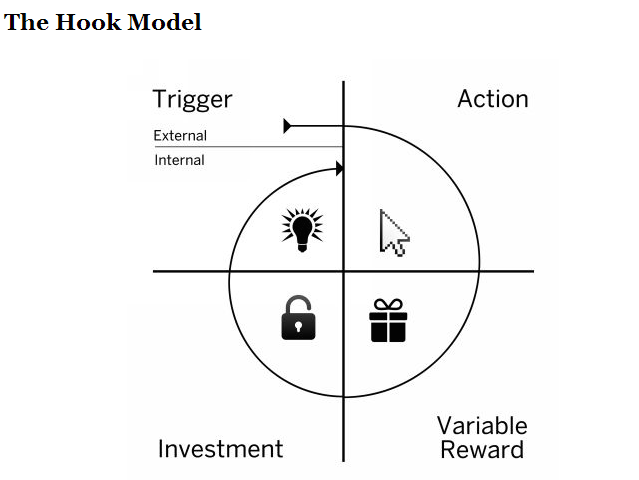

- Read Introduction, understand The Hook Model and its components: External Trigger > Action > Variable Rewards > Investment > Internal Trigger > Repeat

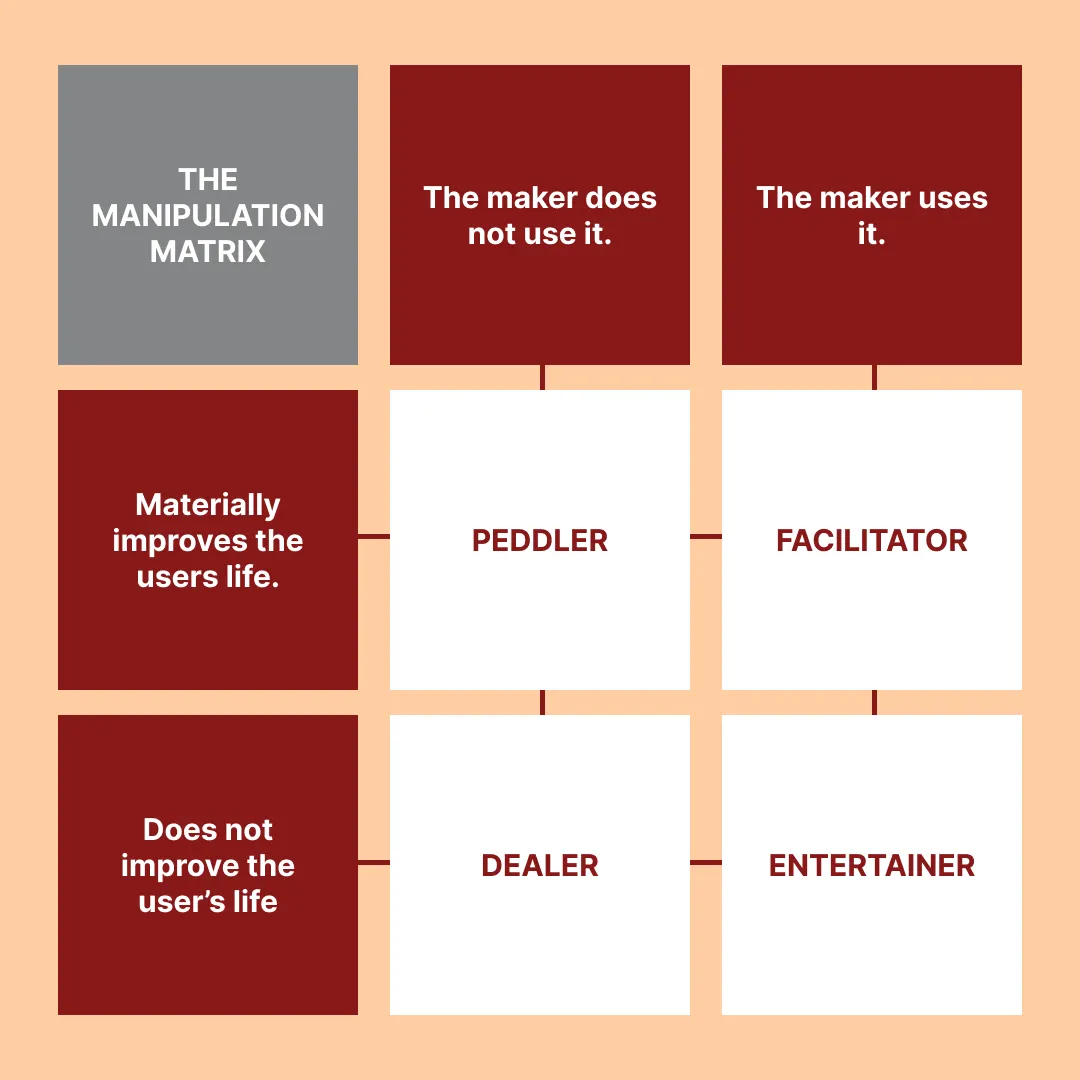

- Read 6. What Are You Going to Do with This?, understand and decide between The Facilitator, Peddler, Entertainer & Dealer

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1. The Habit Zone

- 2. Trigger

- 3. Action

- 4. Variable Reward

- 5. Investment

- 6. What Are You Going to Do with This?

- 8. Habit Testing and Where to Look for Habit-Forming Opportunities

Introduction

95% of smartphone owners check their device within 15 minutes of waking up every morning. Perhaps more startling, fully 1/3 of Americans say they would rather give up sex than lose their cell phones.

A 2011 university study suggested people check their phones 43 times per day. However, industry insiders believe that number is closer to an astounding 150 daily sessions.

Face it: We're hooked.

It's the pull to visit Youtube, Facebook, or Twitter for just a few minutes, only to find yourself still tapping and scrolling an hour later. It's the urge you likely feel throughout your day but hardly notice.

Cognitive psychologists define habits as "automatic behaviors triggered by situational cues": things we do with little or no conscious thought. The products and services we use habitually alter our everyday behavior, just as their designers intended. Our actions have been engineered.

1. Trigger

A trigger is the actuator of behavior-the spark plug in the engine. Triggers come in two types: external and internal." Habit-forming products start by alerting users with external triggers like an email, a Web site link, or the app icon on a phone.

For example, suppose Barbra, a young woman in Pennsylvania, happens to see a photo in her Facebook News Feed taken by a family member from a rural part of the state. It's a lovely picture and because she is planning a trip there with her brother Johnny, the external trigger's call to action (in marketing and advertising lingo) intrigues her and she clicks. By cycling through successive hooks, users begin to form associations with internal triggers, which attach to existing behaviors and emotions.

When users start to automatically cue their next behavior, the new habit becomes part of their everyday routine. Over time, Barbra associates Facebook with her need for social connection. Chapter 2 explores external and internal triggers, answering the question of how product designers determine which triggers are most effective.

2. Action

Following the trigger comes the action: the behavior done in anticipation of a reward. The simple action of clicking on the interesting picture in her news feed takes Barbra to a Web site called Pinterest, a "social bookmarking site with a virtual pinboard."9

This phase of the Hook, as described in chapter 3, draws upon the art and science of usability design to reveal how products drive specific user actions. Companies leverage two basic pulleys of human behavior to increase the likelihood of an action occurring: the ease of performing an action and the psychological motivation to do it.

Once Barbra completes the simple action of clicking on the photo, she is dazzled by what she sees next.

3. Variable Reward

Variable rewards are one of the most powerful tools companies implement to hook users; chapter 4 explains them in further detail. Research shows that levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine surge when the brain is expecting a reward." Although dopamine is often wrongly categorized as making us feel good, introducing variability does create a focused state, which suppresses the areas of the brain associated with judgment and reason while activating the parts associated with wanting and desire. Although classic examples include slot machines and lotteries, variable rewards are prevalent in many other habit-forming products.

When Barbra lands on Pinterest, not only does she see the image she intended to find, but she is also served a multitude of other glittering objects. The images are related to what she is generally interested in-namely things to see on her upcoming trip to rural Pennsylvania-but there are other things that catch her eye as well. The exciting juxtaposition of relevant and irrelevant, tantalizing and plain, beautiful and common, sets her brain's dopamine system aflutter with the promise of reward. Now she's spending more time on Pinterest, hunting for the next wonderful thing to find. Before she knows it, she's spent 45 minutes scrolling.

Chapter 4 also explores why some people eventually lose their taste for certain experiences and how variability impacts their retention.

4. Investment

The last phase of the Hooked Model is where the user does a bit of work. The investment phase increases the odds that the user will make another pass through the cycle in the future. The investment occurs when the user puts something into the product or service such as time, data, effort, social capital, or money.

However, the investment phase isn't about users opening up their wallets and moving on with their day. Rather, the investment implies an action that improves the service for the next go-around. Inviting friends, stating preferences, building virtual assets, and learning to use new features are all investments users make to improve their experience. These commitments can be leveraged to make the trigger more engaging, the action easier, and the reward more exciting with every pass through the Hooked Model. Chapter 5 delves into how investments encourage users to cycle through successive hooks.

As Barbra enjoys scrolling through the Pinterest cornucopia, she builds a desire to keep the things that delight her. By collecting items, she gives the site data about her preferences. Soon she will follow, pin, repin, and make other investments, which serve to increase her ties to the site and prime her for future loops through Pinterest's Hook.

1. The Habit Zone

When I run, I zone out. I don't think about what my body is doing and my mind usually wanders elsewhere. I find it relaxing and refreshing, and run about three mornings each week. Recently, I needed to take an overseas client call during my usual morning run time. "No biggie," I thought. "I can run in the evening instead." However, the time shift created some peculiar behaviors that night.

I left the house for my run at dusk and as I was about to pass a woman taking out her trash, she made eye contact and smiled. I politely saluted her with "Good morning!" and then caught my mistake: "I mean, good evening! Sorry!" I corrected myself, realizing I was about ten hours off. She furrowed her brow and cracked a nervous smile.

Habits are one of the ways the brain learns complex behaviors. Neuroscientists believe habits give us the ability to focus our attention on other things by storing automatic responses in the basal ganglia, an area of the brain associated with involuntary actions."

Habits form when the brain takes a shortcut and stops actively deliberating over what to do next. The brain quickly learns to codify behaviors that provide a solution to whatever situation it encounters.

Why Habits Are Good For Business?

Habit-forming products change user behavior and create unprompted user engagement. The aim is to influence customers to use your product on their own, again and again, without relying on overt calls to actions such as ads or promotions. Once a habit is formed, the user is automatically triggered to use the product during routine events such as wanting to kill time while waiting in line.

Increasing Customer Lifetime Value

Fostering consumer habits is an effective way to increase the value of a company by driving higher customer lifetime value (CLTV): the amount of money made from a customer before that person switches to a competitor, stops using the product, or dies. User habits increase how long and how frequently customers use a product, resulting in higher CLTV.

Some products have a very high CLTV. For example, credit card customers tend to stay loyal for a very long time and are worth a bundle. Hence, credit card companies are willing to spend a considerable amount of money acquiring new customers. This explains why you receive so many promotional offers, ranging from free gifts to airline bonus miles, to entice you to add another card or upgrade your current one. Your potential CLTV justifies a credit card company's marketing investment.

Providing Pricing Flexibility

For example, in the free-to-play video game business, it is standard practice for game developers to delay asking users to pay money until they have played consistently and habitually. Once the compulsion to play is in place and the desire to progress in the game increases, converting users into paying customers is much easier. The real money lies in selling virtual items, extra lives, and special powers.

As of December 2013, more than 500 million people have downloaded Candy Crush Saga, a game played mostly on mobile devices. The game's "freemium" model converts some of those users into paying customers, netting the game's maker nearly $1 million per day.

Supercharging Growth

Users who continuously find value in a product are more likely to tell their friends about it. Frequent usage creates more opportunities to encourage people to invite their friends, broadcast content, and share through word of mouth. Hooked users become brand evangelists-megaphones for your company, bringing in new users at little or no cost.

Products with higher user engagement also have the potential to grow faster than their rivals. Case in point: Facebook leapfrogged its competitors, including MySpace and Friendster, even though it was relatively late to the social networking party. Although its competitors both had healthy growth rates and millions of users by the time Mark Zuckerberg's fledgling site launched beyond the closed doors of academia, his company came to dominate the industry.

Sharpening the Competitive Edge

User habits are a competitive advantage. Products that change customer routines are less susceptible to attacks from other companies.

Gourville claims that for new entrants to stand a chance, they can't just be better, they must be nine times better. Why such a high bar? Because old habits die hard and new products or services need to offer dramatic improvements to shake users out of old routines, Gourville writes that products that require a high degree of behavior change are doomed to fail even if the benefits of using the new product are clear and substantial.

For example, the technology I am using to write this book is inferior to existing alternatives in many ways. I'm referring to the QWERTY keyboard which was first developed in the 1870s for the now-ancient typewriter. QWERTY was designed with commonly used characters spaced far apart. This layout prevented typists from jamming the metal type bars of early machines. This physical limitation is an anachronism in the digital age, yet QWERTY keyboards remain the standard despite the invention of far better layouts. Professor August Dvorak's keyboard design, for example, placed vowels in the center row, increasing typing speed and accuracy. Though patented in 1932, the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard was written off. QWERTY survives due to the high costs of changing user behavior. When first introduced to the keyboard, we use the hunt-and-peck method. After months of practice, we instinctively learn to activate all our fingers in response to our thoughts with little-to-no conscious effort, and the words begin to flow effortlessly from mind to screen. But switching to an unfamiliar keyboard-even if more efficient-would force us to relearn how to type, Fat chance!

As we will learn in chapter 5, users also increase their dependency on habit-forming products by storing value in them-further reducing the likelihood of switching to an alternative. For example, every email sent and received using Google's Gmail is stored indefinitely, providing users with a lasting repository of past conversations. New followers on Twitter increase users' clout and amplify their ability to transmit messages to their communities. Memories on Instagram are added to one's experiences captured digital scrapbook. Switching to a new email service, social network, or photo-sharing app becomes more difficult the more people use them. The nontransferable value created and stored inside these services discourages users from leaving.

Building the Mind Monopoly

Altering behavior requires not only an understanding of how to persuade people to act-for example, the first time they land on a web page-but also necessitates getting them to repeat behaviors for long periods, ideally for the rest of their lives.

The enemy of forming new habits is past behaviors, and research suggests that old habits die hard. Even when we change our routines, neural pathways remain etched in our brains, ready to be reactivated when we lose focus. This presents an especially difficult challenge for product designers trying to create new lines or businesses based on forming new habits.

For new behaviors to really take hold, they must occur often.

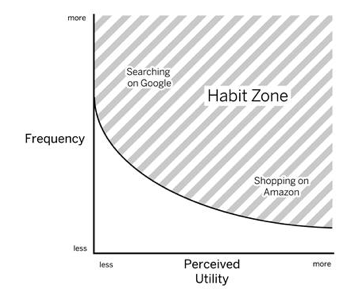

In the Habit Zone

A company can begin to determine its product's habit-forming potential by plotting two factors: frequency (how often the behavior occurs) and perceived utility (how useful and rewarding the behavior is in the user's mind over alternative solutions).

Googling occurs multiple times per day, but any particular search is negligibly better than rival services like Bing. Conversely, using Amazon may be a less frequent occurrence, but users receive great value knowing they'll find whatever they need at the one and only "everything store."

As represented in figure 1, a behavior that occurs with enough frequency and perceived utility enters the Habit Zone, helping to make it a default behavior. If either of these factors falls short and the behavior lies below the threshold, it is less likely that the desired behavior will become a habit.

Note that the line slopes downward but never quite reaches the perceived utility axis. Some behaviors never become habits because they do not occur frequently enough. No matter how much utility is involved, infrequent behaviors remain conscious actions and never create the automatic response that is characteristic of habits. On the other axis, however, even a behavior that provides minimal perceived benefit can become a habit simply because it occurs frequently.

Remember, the Hooked Model does not get people to do things they don't want to do. Your product must ultimately be useful. The Habit Zone is meant to be a guiding theory, and the scale of the illustration is intentionally left blank. Unfortunately for companies, research thus far has not found a universal timescale for turning all behaviors into habits. A 2010 study found that some habits can be formed in a matter of weeks while others can take more than five months. The researchers also found that the complexity of the behavior and how important the habit was to the person greatly affected how quickly the routine was formed.

There are few rules when it comes to answering "How frequent is frequent enough?" and the answer is likely specific to each business and behavior. However, as the previously mentioned flossing study demonstrates, we know that higher frequency is better.

Think of the products and services you would identify as habit forming. Most of these are used daily, if not multiple times per day. Let's explore why we use these products so frequently.

Vitamins Versus Painkillers

"Are you building a vitamin or painkiller?" is a common, almost clichéd question many investors ask founders eager to cash their first venture capital check. The correct answer, from the perspective of most investors, is the latter: a painkiller. Likewise, innovators in companies big and small are constantly asked to prove their idea is important enough to merit the time and money needed to build it. Gatekeepers such as investors and managers want to invest in solving real problems or meeting immediate needs by backing painkillers.

Painkillers solve an obvious need, relieving a specific pain, and often have quantifiable markets. Think Tylenol, the brand-name version of acetaminophen, and the product's promise of reliable relief. It's the kind of ready-made solution for which people are happy to pay.

Vitamins, by contrast, do not necessarily solve an obvious pain point. Instead they appeal to users' emotional rather than functional needs. When we take our multivitamin each morning, we don't really know if it is actually making us healthier. In fact, recent evidence shows taking multivitamins may actually be doing more harm than good.

But we don't really care, do we? Efficacy is not why we take vitamins. Taking a vitamin is a "check it off your list" behavior we measure in terms of psychological, rather than physical, relief. We feel satisfied that we are doing something good for our bodies-even if we can't tell how much good it is actually doing us. Unlike a painkiller, without which we cannot function, missing a few days of vitamin popping, say while on vacation, is no big deal.

My answer to the vitamin versus painkiller question: Habit-forming technologies are both. These services seem at first to be offering nice-to-have vitamins, but once the habit is established, they provide an ongoing pain remedy.

2. Trigger

Habits are like pearls. Oysters create natural pearls by accumulating layer upon layer of a nacre called mother-of-pearl, eventually forming the smooth treasure over several years. But what causes the nacre to begin forming a pearl? The arrival of a tiny irritant, such as a piece of grit or an unwelcome parasite, triggers the oyster's system to begin blanketing the invader with layers of shimmery coating.

Similarly, new habits need a foundation upon which to build. Triggers provide the basis for sustained behavior change.

Reflect on your own life for a moment. What woke you up this morning? What caused you to brush your teeth? What brought you to read this book?

Triggers take the form of obvious cues like the morning alarm clock but also come as more subtle, sometimes subconscious signals that just as effectively influence our daily behavior. A trigger is the actuator of behavior-the grit in the oyster that precipitates the pearl. Whether we are cognizant of them or not, triggers move us to take action.

Triggers come in two types: external and internal.

External Triggers

External triggers are embedded with information, which tells the user what to do next.

1. Paid Triggers

Advertising, search engine marketing, and other paid channels are commonly used to get users' attention and prompt them to act. Paid triggers can be effective but costly ways to keep users coming back. Habit-forming companies tend not to rely on paid triggers for very long, if at all. Imagine if YouTube, Slack, or Instagram needed to buy an ad to prompt users to revisit their sites-these companies would soon go broke.

Because paying for re-engagement is unsustainable for most business models, companies generally use paid triggers to acquire new users and then leverage other triggers to bring them back.

2. Earned Triggers

Earned triggers are free in that they cannot be bought directly, but they often require investment in the form of time spent on public and media relations. Favorable press mentions, hot viral videos, and featured app store placements are all effective ways to gain attention. Companies may be lulled into thinking that related downloads or sales spikes signal long-term success, yet awareness generated by earned triggers can be short-lived.

For earned triggers to drive ongoing user acquisition, companies must keep their products in the limelight-a difficult and unpredictable task.

3. Relationship Triggers

One person telling others about a product or service can be a highly effective external trigger for action. Whether through an electronic invitation, a Facebook "like," or old fashioned word of mouth, product referrals from friends and family are often a key component of technology diffusion.

Relationship triggers can create the viral hyper-growth entrepreneurs and investors lust after. Sometimes relationship triggers drive growth because people love to tell one another about a wonderful offer.

Proper use of relationship triggers requires building an engaged user base that is enthusiastic about sharing the benefits of the product with others.

4. Owned Triggers

Owned triggers consume a piece of real estate in the user's environment. They consistently show up in daily life and it is ultimately up to the user to opt in to allowing these triggers to appear.

For example, an app icon on the user's phone screen, an e-mail newsletter to which the user subscribes, or an app update notification only appears if the user wants it there. As long as the user agrees to see the trigger, the company that sets the trigger owns a share of the user's attention.

Owned triggers are only set after users sign up for an account, submit their e-mail address, install an app, opt in to newsletters, or otherwise indicate they want to continue receiving communications.

While paid, earned, and relationship triggers drive new user acquisition, owned triggers prompt repeat engagement until a habit is formed. Without owned triggers and users' tacit permission to enter their attentional space, it is difficult to cue users frequently enough to change their behavior.

Yet external triggers are only the first step. The ultimate goal of all external triggers is to propel users into and through the Hooked Model so that, after successive cycles, they do not need further prompting from external triggers. When users form habits, they are cued by a different kind of trigger: internal ones.

Internal Triggers

When a product becomes tightly coupled with a thought, an emotion, or a preexisting routine, it leverages an internal trigger.

Internal triggers manifest automatically in your mind. Connecting internal triggers with a product is the brass ring of habit-forming technology.

Emotions, particularly negative ones, are powerful internal triggers and greatly influence our daily routines. Feelings of boredom, loneliness, frustration, confusion, and indecisiveness often instigate a slight pain or irritation and prompt an almost instantaneous and often mindless action to quell the negative sensation. For instance, Yin often uses Instagram when she fears a special moment will be lost forever.

Positive emotions can also serve as internal triggers, and may even be triggered themselves by a need to satisfy something that is bothering us. After all, we use products to find solutions to problems. The desire to be entertained can be thought of as the need to satiate boredom. A need to share good news can also be thought of as an attempt to find and maintain social connections.

As product designers it is our goal to solve these problems and eliminate pain-to scratch the user's itch. Users who find a product that alleviates their pain will form strong, positive associations with the product over time. After continued use, bonds begin to form-like the layers of nacre in an oyster-between the product and the user whose need it satisfies.

Gradually, these bonds cement into a habit as users turn to your product when experiencing certain internal triggers.

To ameliorate the sensation of uncertainty, Google is just a click away. E-mail, perhaps the mother of all habit-forming technology, is a go-to solution for many of our daily agitations, from validating our importance (or even our existence) by checking to see if someone needs us, to providing an escape from life's more mundane moments.

Once we're hooked, using these products does not always require an explicit call to action. Instead, they rely upon our automatic responses to feelings that precipitate the desired behavior. Products that attach to these internal triggers provide users with quick relief. Once a technology has created an association in users' minds that the product is the solution of choice, they return on their own, no longer needing prompts from external triggers.

In the case of internal triggers, the information about what to do next is encoded as a learned association in the user's memory.

The association between an internal trigger and your product, however, is not formed overnight. It can take weeks or months of frequent usage for internal triggers to latch onto cues. New habits are sparked by external triggers, but associations with internal triggers are what keeps users hooked.

Building for Triggers

Products that successfully create habits soothe the user's pain by laying claim to a particular feeling. To do so, product designers must know their user's internal triggers-that is, the pain they seek to solve. Finding customers' internal triggers requires learning more about people than what they can tell you in a survey, though. It requires digging deeper to understand how your users feel.

The ultimate goal of a habit-forming product is to solve the user's pain by creating an association so that the user identifies the company's product or service as the source of relief.

First, the company must identify the particular frustration or pain point in emotional terms, rather than product features. How do you, as a designer, go about uncovering the source of a user's pain? The best place to start is to learn the drivers behind successful habit-forming products-not to copy them, but to understand how they solve users' problems. Doing so will give you practice in diving deeper into the mind of the consumer and alert you to common human needs and desires.

As Evan Williams, cofounder of Blogger and Twitter said, the Internet is "a giant machine designed to give people what they want." Williams continued, "We often think the Internet enables you to do new things... But people just want to do the same things they've always done."

These common needs are timeless and universal. Yet talking to users to reveal these wants will likely prove ineffective because they themselves don't know which emotions motivate them. People just don't think in these terms. You'll often find that people's declared preferences-what they say they want are far different from their revealed preferences-what they actually do.

What would your users want to achieve by using your solution? Where and when will they use it? What emotions influence their use and will trigger them to action?

When it comes to figuring out why people use habit-forming products, internal triggers are the root cause, and "Why?" is a question that can help drill right to the core.

For example, let's say we're building a fancy new technology called e-mail for the first time. The target user is a busy middle manager named Julie. We've built a detailed narrative of our user, Julie, that helps us answer the following series of whys:

Why #1: Why would Julie want to use e-mail?

Answer: So she can send and receive messages.

Why #2: Why would she want to do that?

Answer: Because she wants to share and receive information quickly.

Why #3: Why does she want to do that?

Answer: To know what's going on in the lives of her coworkers, friends, and family.

Why #4: Why does she need to know that?

Answer: To know if someone needs her.

Why #5: Why would she care about that?

Answer: She fears being out of the loop.

Now we've got something! Fear is a powerful internal trigger and we can design our solution to help calm Julie's fear. Naturally, we might have come to another conclusion by starting with a different persona, varying the narrative, or coming up with different hypothetical answers along the chain of whys. Only an accurate understanding of our user's underlying needs can inform the product requirements.

3. Action

The next step in the Hooked Model is the action phase. The trigger, driven by internal or external cues, informs the user of what to do next; however, if the user does not take action, the trigger is useless. To initiate action, doing must be easier than thinking. Remember, a habit is a behavior clone with little or no conscious thought. The more effort-either physical or mental-required to perform the desired action, the less likely it is to occur.

Action Versus Inaction

If action is paramount to habit formation, how can a product designer influence users to act? Is there a formula for behavior? It turns out that there is.

(1) the user must have sufficient motivation

(2) the user must have the ability to complete the desired action

(3) a trigger must be present to activate the behavior

The Fogg Behavior Model is represented in the formula B = MAT, which represents that a given behavior will occur when motivation, ability, and a trigger are present at the same time and in sufficient degrees. If any component of this formula is missing or inadequate, the user will not cross the "Action Line" and the behavior will not occur.

Motivation

Fogg states that all humans are motivated to seek pleasure and avoid pain; to seek hope and avoid fear; and finally, to seek social acceptance and avoid rejection. The two sides of the three Core Motivators can be thought of as levers to increase or decrease the likelihood of someone's taking a particular action by increasing or decreasing that person's motivation.

Motivation Examples in Advertising

Perhaps no industry makes the elements of motivation more explicit than the advertising business. Advertisers regularly tap into people's motivations to influence their habits. By looking at ads with a critical eye, we can identify how they attempt to influence our actions.

Another example of motivation in advertising relates to the old saying "Sex sells." Long an advertising standard, images of buff, scantily clad (and usually female) bodies are used to hawk everything from the latest Victoria's Secret lingerie to domain names through GoDaddy .com and fast food chains such as Carl's Jr. and Burger King. These and countless other ads use the voyeuristic promise of pleasure to capture attention and motivate action.

Naturally, this strategy only appeals to a particular demographic's association with sex as a salient motivator. While teenage boys-the common target for such ads-may find them inspiring, others may find them distasteful. What motivates some people will not motivate others, a fact that provides all the more reason to understand the needs of your particular audience.

While internal triggers are the frequent, everyday itch experienced by users, the right motivators create action by offering the promise of desirable outcomes (i.e., a satisfying scratch).

Ability

Consequently, any technology or product that significantly reduces the steps to complete a task will enjoy high adoption rates by the people it assists.

Take a human desire, preferably one that has been around for a really long time... Identify that desire and use modern technology to take out steps.

Elements Of Simplicity

(1) Time: how long it takes to complete an action.

(2) Money: the fiscal cost of taking an action.

(3) Physical effort: the amount of labor involved in taking the action.

(4) Brain cycles: the level of mental effort and focus required to take an action.

(5) Social deviance: how accepted the behavior is by others.

(6) Non-routine: How much the action matches or disrupts existing routines.

To increase the likelihood that a behavior will occur, Fogg instructs designers to focus on simplicity as a function of the user's scarcest resource at that moment. In other words: Identify what the user is missing. What is making it difficult for the user to accomplish the desired action?

Is the user short on time? Is the behavior too expensive? Is the user exhausted after a long day of work? Is the product too difficult to understand? Is the user in a social context where the behavior could be perceived as inappropriate? Is the behavior simply so far removed from the user's normal routine that its strangeness is off-putting?

These factors will differ by person and context; therefore, designers should ask, "What is the thing that is missing that would allow my users to proceed to the next step?" Designing with an eye toward simplifying the overall user experience reduces friction, removes obstacles, and helps push the user across Fogg's action line.

The action phase of the Hooked Model incorporates Fogg's six elements of simplicity by asking designers to consider how their technology can facilitate the simplest action in anticipation of reward. The easier an action, the more likely the user is to do it and to continue the cycle through the next phase of the Hooked Model.

On Heuristics and Perception

The Scarcity Effect

In 1975 researchers Stephen Worchel, Jerry Lee, and Akanbi Adewole wanted to know how people would value cookies in two identical glass jars. One jar held ten cookies while the other contained just two. Which cookies would people value more?

Although the cookies and jars were identical, participants valued the ones in the near-empty jar more highly.

The appearance of scarcity affected their perception of value.

The Framing Effect

The mind takes shortcuts informed by our surroundings to make quick and sometimes erroneous judgments.

When Bell performed his concert in the subway station, few stopped to listen. But when framed in the context of a concert hall, he can charge beaucoup bucks.

The Anchoring Effect

Rarely can you walk into a clothing store without seeing signage for "30% off," "buy one, get one free," and other sales and deals. In reality these items are often marketed to maximize profits for the business. The same store often has similar but less expensive (yet not discounted) products. I recently visited a store that offered a package of three Jockey brand undershirts at a "buy one, get one half-off" discount for $29.50. After surveying other options I noticed a package of five Fruit of the Loom brand undershirts selling for $34. After doing some quick math I discovered that the undershirts not on sale were actually cheaper per shirt than the discounted brand's package.

People often anchor to one piece of information when making a decision.

The Endowed Progress Effect

Two groups of customers were given punch cards awarding a free car wash once the cards were fully punched. One group was given a blank punch card with eight squares; the other was given a punch card with ten squares that came with two free punches. Both groups still had to purchase eight car washes to receive a free wash; however, the second group of customers-those that were given two free punches-had a staggering 82 percent higher completion rate.

The study demonstrates the endowed progress effect, a phenomenon that increases motivation as people believe they are nearing a goal.

4. Variable Reward

Understanding Rewards

The study revealed that what draws us to act is not the sensation we receive from the reward itself, but the need to alleviate the craving for that reward.

Without variability we are like children in that once we figure out what will happen next, we become less excited by the experience. The same rules that apply to puppies also apply to products. To hold our attention, products must have an ongoing degree of novelty.

Our brains have evolved over millennia to help us figure out how things work. Once we understand causal relationships, we retain that information in memory. Our habits are simply the brain's ability to quickly retrieve the appropriate behavioral response to a routine or process we have already learned. Habits help us conserve our attention for other things while we go about the tasks we perform with little or no conscious thought.

However, when something breaks the cause-and-effect pattern we've come to expect-when we encounter something outside the norm-we suddenly become aware of it again. Novelty sparks our interest, makes us pay attention, and-like a baby encountering a friendly dog for the first time-we seem to love it.

Rewards of the Tribe

We are a species that depends on one another. Rewards of the tribe, or social rewards, are driven by our connectedness with other people.

Our brains are adapted to seek rewards that make us feel accepted, attractive, important, and included.

Many of our institutions and industries are built around this need for social reinforcement. From civic and religious groups to spectator sports and "watercooler" television shows, the need to feel social connectedness shapes our values and drives much of how we spend our time.

It is no surprise that social media has exploded in popularity. Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and several other sites collectively provide over a billion people with powerful social rewards on a variable schedule. With every post, tweet, or pin, users anticipate social validation. Rewards of the tribe keep users coming back, wanting more.

Examples: Facebook, StackOverflow, League of Legends

Rewards of the Hunt

The need to acquire physical objects, such as food and other supplies that aid our survival, is part of our brain's operating system.

Where we once hunted for food, today we hunt for other things. In modern society, food can be bought with cash, and more recently by extension, information translates into money.

Examples: Machine gambling, Twitter, Pinterest

Rewards of the Self

Finally, there are the variable rewards we seek for a more personal form of gratification. We are driven to conquer obstacles, even if just for the satisfaction of doing so. Pursuing a task to completion can influence people to continue all sorts of behaviors. 18 Surprisingly, we even pursue these rewards when we don't outwardly appear to enjoy them. For example, watching someone investing countless hours into completing a tabletop puzzle can reveal frustrated face contortions and even sounds of muttered profanity. Although puzzles offer no prize other than the satisfaction of completion, for some the painstaking search for the right pieces can be a wonderfully mesmerizing struggle.

The rewards of the self are fueled by "intrinsic motivation" as highlighted by the work of Edward Deci and Richard Ryan. Their self-determination theory espouses that people desire, among other things, to gain a sense of competency. Adding an element of mystery to this goal makes the pursuit all the more enticing.

Examples: video games, emails (inbox-zero), CodeAcademy

Important Considerations for Designing Reward Systems

Variable Rewards Are not a Free Pass

Recently, gamification-defined as the use of gamelike elements in nongame environments-has been used with varying success. Points, badges, and leaderboards can prove effective, but only if they scratch the user's itch. When there is a mismatch between the customer's problem and the company's assumed solution, no amount of gamification will help spur engagement. Likewise, if the user has no ongoing itch at all-say, no need to return repeatedly to a site that lacks any value beyond the initial visit-gamification will fail because of a lack of inherent interest in the product or service offered. In other words, gamification is not a "one size fits all" solution for driving user engagement.

Variable rewards are not magic fairy dust that a product designer can sprinkle onto a product to make it instantly more attractive. Rewards must fit into the narrative of why the product is used and align with the user's internal triggers and motivations. They must ultimately improve the user's life.

Maintain a Sense of Autonomy

I soon began to feel obligated to confess my mealtime transgressions to my phone. MyFitnessPal became MyFitnessPain. Yes, I had chosen to install the app at first, but despite my best intentions, my motivation faded and using the app became a chore. Adopting a weird new behavior-calorie tracking, in my case-felt like something I had to do, not something I wanted to do. My only options were to comply or quit; I chose the latter.

Companies that successfully change behaviors present users with an implicit choice between their old way of doing things and a new, more convenient way to fulfill existing needs.

By maintaining the users' freedom to choose, products can facilitate the adoption of new habits and change behavior for good.

Beware of Finite Variability

Experiences with finite variability become less engaging because they eventually become predictable.

Businesses with finite variability are not inferior per se; they just operate under different constraints. They must constantly churn out new content and experiences to cater to their consumers' insatiable desire for novelty. It is no coincidence that both Hollywood and the video gaming industry operate under what is called the studio model, whereby a deep-pocketed company provides backing and distribution to a portfolio of movies or games, uncertain which one will become the next megahit.

While content consumption, like watching a TV show, is an example of finite variability, content creation is infinitely variable. Sites like Dribbble, a platform for designers and artists to showcase their work, exemplify the longer-lasting engagement that comes from infinite variability. On the site contributors share their designs in search of feedback from other artists. As new trends and design patterns change, so do Dribbble's pages. The variety of what Dribbble users can create is limitless, and the constantly changing site always offers new surprises.

Platforms like YouTube, Facebook, Pinterest, and Twitter all leverage user-generated content to provide visitors with a never-ending stream of newness. Naturally, even sites utilizing infinite variability are not guaranteed to hold on to users forever. Eventually to borrow from the title of Michael Lewis's 1999 book about the dot-com boom in Silicon Valley-the "new new thing" comes along and consumers migrate to it for the reasons discussed in earlier chapters. However, products utilizing infinite variability stand a better chance of holding on to users' attention, while those with finite variability must constantly reinvent themselves just to keep pace.

Inherent Variability

For companies like Google and Uber, adding more variability to an inherently variable user experience makes no sense. Can you imagine what would happen if your Uber driver decided to take you for a spin around the block just for fun?

Remember, variability is only engaging when the user maintains a sense of autonomy. People will stand in line for hours to ride the twists and turns of a roller coaster but are panic stricken when they experience a bit of turbulence on an airline flight. Therefore, the job of companies operating in conditions of inherent variability is to give users what they desperately crave in conditions of low control-a sense of agency.

5. Investment

Changing Attitude

The more users invest time and effort into a product or service, the more they value it. In fact, there is ample evidence to suggest that labor leads to love.

We Irrationally Value Our Efforts

IKEA, the world's largest furniture retailer, sells affordable, ready-to-assemble household furnishings. The Swedish company's key innovation is its packaging process, which allows the company to decrease labor costs, increase distribution efficiency, and better utilize the real estate in its stores.

Unlike its competitors who sell preassembled merchandise, IKEA puts its customers to work. It turns out there's a hidden benefit to making users invest physical effort in assembling the product-by asking customers to assemble their own furniture, Ariely believes they adopt an irrational love of the furniture they built, just like the test subjects did in the origami experiments. Businesses that leverage user effort confer higher value to their products simply because their users have put work into them. The users have invested in the products through their labor.

We Seek to Be Consistent with Our Past Behaviors

Studies reveal that our past is an excellent predictor of our future.

We Avoid Cognitive Dissonance

Consider your reaction the first time you sipped a beer or tried spicy food. Was it tasty? Unlikely. Our bodies are designed to reject alcohol and capsaicin, the compound that creates the sensation of heat in spicy food. Our innate reaction to these acquired tastes is to reject them, yet we learn to like them through repeated exposure. We see others enjoying them, try a little more, and over time condition ourselves. To avoid the cognitive dissonance of not liking something that others seem to take so much pleasure in, we slowly change our perception of the thing we once did not enjoy.

Together, the three tendencies just described influence our future actions: The more effort we put into something, the more likely we are to value it; we are more likely to be consistent with our past behaviors; and finally, we change our preferences to avoid cognitive dissonance.

Also in contrast to the action phase, the investment phase increases friction. This certainly breaks conventional thinking in the product design community that all user experiences should be as easy and effortless as possible. This approach still generally holds true, as does my advice in the action phase to make the intended actions as simple as possible. In the investment phase, however, asking users to do a bit of work comes after users have received variable rewards, not before. The timing of asking for user investment is critically important. By asking for the investment after the reward, the company has an opportunity to leverage a central trait of human behavior.

The big idea behind the investment phase is to leverage the user's understanding that the service will get better with use (and personal investment). Like a good friendship, the more effort people put in, the more both parties benefit.

Storing Value

The stored value users put into the product increases the likelihood they will use it again in the future and comes in a variety of forms.

Content

Every time users of Spotify listen to music using the streaming service, they strengthen their ties to the product. Neither Spotify nor their users created the songs, yet the more users consume content, the more valuable the service becomes.

Spotify uses the small investment of songs played in order to assemble a selection of tunes users haven't previously heard but are likely to enjoy, called "Discover Weekly". With continued investment, the service gets better at learning users' tastes and provides tailor-made suggestions.

The collection of memories and experiences, in aggregate, becomes more valuable over time and the service becomes harder to leave as users' personal investment in the site grows.

Data

Information generated, collected, or created by users (e.g., songs, photos, or news clippings) are examples of stored value in the form of content. Sometimes, though, users invest in a service by either actively or passively adding their own personal data.

On LinkedIn the user's online résumé embodies the concept of data as stored value. Every time job seekers use the service, they are prompted to add more information.

The company found that the more information users invested in the site, the more committed they became to it.

As Josh Elman, an early senior product manager at the company, told me, "If we could get users to enter just a little information, they were much more likely to return." The tiny bit of effort associated with providing more user data created a powerful hook to bring people back to the service.

Followers

Investing in following the right people increases the value of the product by displaying more relevant and interesting content in each user's Twitter feed. It also tells Twitter a lot about its users, which in turn improves the service overall.

Reputation

Reputation is a form of stored value users can literally take to the bank. On online marketplaces such as eBay, Upwork, Yelp, and Airbnb, people with negative scores are treated very differently from those with good reputations. It can often be the deciding factor in what price a seller gets for an item on eBay, who is selected for an Upwork job, which restaurants appear at the top of Yelp search results, and the price of a room rental on Airbnb.

On eBay both buyers and sellers take their reputations very seriously. The e-commerce giant surfaces user-generated quality scores for every buyer and seller, and awards its most active users with badges to symbolize their trustworthiness. Businesses with bad reputations find it difficult, if not impossible, to compete against highly rated sellers. Reputation is a form of stored value that increases the likelihood of using a service.

Reputation makes users, both buyers and sellers, more likely to stick with whichever service they have invested their efforts in to maintain a high-quality score.

Skill

Investing time and effort into learning to use a product is a form of investment and stored value. Once a user has acquired a skill, using the service becomes easier and moves them to the right on the ability axis of the Fogg Behavior Model we discussed in chapter 3. As Fogg describes it, non-routine is a factor of simplicity, and the more familiar a behavior is, the more likely the user is to do it.

For example, Adobe Photoshop is the most widely used professional graphics editing program in the world. The software provides hundreds of advanced features for creating and manipulating images. Learning the program is difficult at first, but as users become more familiar with the product often investing hours watching tutorials and reading how-to guides their expertise and efficiency using the product improves. They also achieve a sense of mastery.

Once users have invested the effort to acquire a skill, they are less likely to switch to a competing product.

Loading the Next Trigger

As described in chapter 2, triggers bring users back to the product. Ultimately, habit-forming products create a mental association with an internal trigger. Yet to create the habit, users must first use the product through multiple cycles of the Hooked Model. Therefore, external triggers must be used to bring users back around again to start another cycle.

Habit-forming technologies leverage the user's past behavior to initiate an external trigger in the future.

Users set future triggers during the investment phase, providing companies with an opportunity to reengage the user. We will now explore a few examples of how companies have helped load the next trigger during the investment phase.

6. What Are You Going to Do with This?

The Hooked Model is designed to connect the user's problem with the designer's solution frequently enough to form a habit. It is a framework for building products that solve user needs through long-term engagement.

As users pass through cycles of the Hooked Model, they learn to meet their needs with the habit-forming product. Effective hooks transition users from relying upon external triggers to cueing mental associations with internal triggers. Users move from states of low engagement to high engagement, from low preference to high preference.

You are now equipped to use the Hooked Model to ask yourself these fundamental questions for building effective hooks:

- What do users really want? What pain is your product relieving? (Internal trigger)

- What brings users to your service? (External trigger)

- What is the simplest action users take in anticipation of reward, and how can you simplify your product to make this action easier? (Action)

- Are users fulfilled by the reward yet left wanting more? (Variable reward)

- What "bit of work" do users invest in your product? Does it load the next trigger and store value to improve the product with use? (Investment)

The Morality of Manipulation

Manipulation is an experience crafted to change behavior-we all know what it feels like. We're uncomfortable when we sense someone is trying to make us do something we wouldn't do otherwise, like when sitting through a car salesman's spiel or hearing a time-share presentation.

I offer the Manipulation Matrix, a simple decision-support tool entrepreneurs, employees, and investors can use long before product is shipped or code is written. The Manipulation Matrix does not try to answer which businesses are moral or which will succeed, nor does it describe what can and cannot become a habit-forming technology. The matrix seeks to help you answer not "Can I hook my users?" but instead "Should I attempt to?"

1. The Facilitator

When you create something that you would use, that you believe makes the user's life better, you are facilitating a healthy habit. It is important to note that only you can decide if you would actually use the product or service, and what "materially improving the life of the user" really means in light of what you are creating.

If you find yourself squirming as you ask yourself these questions or needing to qualify or justify your answers, stop! You failed. You have to truly want to use the product and believe it materially benefits your life as well as the lives of your users.

The role of facilitator fulfills the moral obligation for entrepreneurs building a product they will themselves use and that they believe materially improves the lives of others. As long as they have procedures in place to assist those who form unhealthy addictions, the designer can act with a clean conscience. To take liberties with Mahatma Gandhi's famous quote, facilitators "build the change they want to see in the world."

2. The Peddler

Fitness apps, charity Web sites, and products that claim to suddenly turn hard work into fun often fall into this quadrant. Possibly the most common example of peddlers, though, is in advertising.

Countless companies convince themselves they're making ad campaigns users will love. They expect their videos to go viral and their branded apps to be used daily. Their so-called reality distortion fields keep them from asking the critical question, "Would I actually find this useful?" The answer to this uncomfortable question is nearly always no, so they twist their thinking until they can imagine a user they believe might find the ad valuable.

Materially improving users' lives is a tall order, and attempting to create a persuasive technology that you do not use yourself is incredibly difficult. This puts designers at a heavy disadvantage because of their disconnect with their products and users. There's nothing immoral about peddling, in fact, many companies working on solutions for others do so out of purely altruistic reasons. It's just that the odds of successfully designing products for a customer you don't know extremely well are depressingly low.

Peddlers tend to lack the empathy and insights needed to create something users truly want.

Often the peddler's project results in a time-wasting failure because the designers did not fully understand their users. As a result, no one finds the product useful.

3. The Entertainer

Sometimes makers of products just want to have fun. If creators of a potentially addictive technology make something that they use but can't in good conscience claim improves users' lives, they're making entertainment.

Entertainment is art and is important for its own sake. Art provides joy, helps us see the world differently, and connects us with the human condition. These are all important and age-old pursuits. Entertainment, however, has particular attributes of which the entrepreneur, employee, and investor should be aware when using the Manipulation Matrix.

Art is often fleeting; products that form habits around entertainment tend to fade quickly from users' lives. A hit song, repeated over and over again in the mind, becomes nostalgia after it is replaced by the next chart-topper. A book like this one is read and thought about for a while until the next interesting piece of brain candy comes along.

Entertainment is a hits-driven business because the brain reacts to stimulus by wanting more and more of it, ever hungry for continuous novelty.

Building an enterprise on ephemeral desires is akin to running on an incessantly rolling treadmill: You have to keep up with the constantly changing demands of your users.

In this quadrant the sustainable business is not purely the game, the song, or the book-profit comes from an effective distribution system for getting those goods to market while they're still hot, and at the same time keeping the pipeline full of fresh releases to feed an eager audience.

4. The Dealer

Creating a product that the designer does not believe improves users' lives and that he himself would not use is called exploitation.

In the absence of these two criteria, presumably the only reason the designer is hooking users is to make a buck. Certainly, there is money to be made getting users to do things that do little more than extract cash; and where there is cash, there will be someone willing to take it.

The question is: Is that someone you? Casinos and drug dealers offer users a good time, but when the action harms the user, the fun stops.

8. Habit Testing and Where to Look for Habit-Forming Opportunities

Does your users' internal trigger frequently prompt them to action? Is your external trigger cueing them when they are most likely to act? Is your design simple enough to make taking the action easy? Does the reward satisfy your users' need while leaving them wanting more? Do your users invest a bit of work in the product, storing value to improve the experience with use and loading the next trigger?

By identifying where your product or service is lacking, you can focus on developing improvements to your product where it matters most.

Habit Testing

The Hooked Model can be a helpful tool for filtering out bad ideas with low habit potential as well as a framework for identifying room for improvement in existing products.

However, after the designer has formulated new hypotheses, there is no way to know which ideas will work without testing them with actual users.

Building a habit-forming product is an iterative process and requires user-behavior analysis and continuous experimentation.

Through my studies and discussions with entrepreneurs at today's most successful habit-forming companies, I've distilled this process into what I term Habit Testing. It is a process inspired by the "build, measure, learn" methodology championed by the lean start-up movement. Habit Testing offers insights and actionable data to inform the design of habit-forming products. It helps clarify who your devotees are, what parts (if any) of your product are habit forming, and why those aspects of your product are changing user behavior.

Step 1: Identify

The initial question for Habit Testing is "Who are the product's habitual users?" Remember, the more frequently your product is used, the more likely it is to form a user habit.

First, define what it means to be a devoted user. How often "should" one use your product?

The answer to this question is very important and can widely change your perspective. Publicly available data from similar products or solutions can help define your users and engagement targets. If data are not available, educated assumptions must be made—but be realistic and honest.

Once you know how often users should use your product, dig into the numbers to identify how many and which type of users meet this threshold. As a best practice, use cohort analysis to measure changes in user behavior through future product iterations.

Step 2: Codify

Let's say that you've identified a few users who meet the criteria of habitual users. Yet how many such users are enough? My rule of thumb is 5%. Though your rate of active users will need to be much higher to sustain your business, this is a good initial benchmark.

However, if at least 5% of your users don't find your product valuable enough to use as much as you predicted they would, you may have a problem. Either you identified the wrong users or your product needs to go back to the drawing board. If you have exceeded that bar, though, and identified your habitual users, the next step is to codify the steps they took using your product to understand what hooked them.

Users will interact with your product in slightly different ways. Even if you have a standard user flow, the way users engage with your product creates a unique fingerprint. Where users are coming from, decisions made when registering, and the number of friends using the service are just a few of the behaviors that help create a recognizable pattern. Sift through the data to determine if similarities emerge.

You are looking for a Habit Path-a series of similar actions shared by your most loyal users.

For example, in its early days, Twitter discovered that once new users followed 30 other members, they hit a tipping point that dramatically increased the odds they would keep using the site.

Every product has a different set of actions that devoted users take; the goal of finding the Habit Path is to determine which of these steps is critical for creating devoted users so that you can modify the experience to encourage this behavior.

Step 3: Modify

Armed with new insights, it is time to revisit your product and identify ways to nudge new users down the same Habit Path taken by devotees. This may include an update to the registration funnel, content changes, feature removal, or increased emphasis on an existing feature. Twitter used the insights gained from the previous step to modify its on-boarding process, encouraging new users to immediately begin following others.

Habit Testing is a continual process you can implement with every new feature and product iteration.

Tracking users by cohort and comparing their activity with that of habitual users should guide how products evolve and improve.

Discovering Habit-forming Opportunities

Paul Graham advises entrepreneurs to leave the sexy-sounding business ideas behind and instead build for their own needs: "Instead of asking 'what problem should I solve?' ask 'what problem do I wish someone else would solve for me?"

Studying your own needs can lead to remarkable discoveries and new ideas because the designer always has a direct line to at least one user: him or herself.

As you go about your day, ask yourself why you do or do not do certain things and how those tasks could be made easier or more rewarding.

Observing your own behavior can inspire the next habit-forming product or inform a breakthrough improvement to an existing solution.

Nascent Behaviors

Sometimes technologies that appear to cater to a niche will cross into the mainstream. Behaviors that start with a small group of users can expand to a wider population, but only if they cater to a broad need. However, the fact that the technology is at first used only by a small population often deceives observers into dismissing the product's true potential.

Naturally, now we do read books and newspapers over the Internet. When technologies are new, people are often skeptical. Old habits die hard and few people have the foresight to see how new innovations will eventually change their routines. However, by looking to early adopters who have already developed nascent behaviors, entrepreneurs and designers can identify niche use cases, which can be taken mainstream.

For example, in its early days, Facebook was only used by Harvard students. The service mimicked an offline behavior familiar to all college students at the time: perusing a printed book of student faces and profiles. After finding popularity at Harvard, Facebook rolled out to other Ivy League schools, then to college students nationwide. Next came high school kids and later, employees at select companies. Finally, in September 2006, Facebook was opened to the world. Currently, over two billion people use Facebook.

What first began as a nascent behavior at one campus became a global phenomenon catering to the fundamental human need for connection to others.

As discussed in the first chapter, many habit-forming technologies begin as vitamins-nice-to-have products that, over time, become must-have painkillers by relieving an itch or pain. It is revealing that so many breakthrough technologies and companies, from airplanes to Airbnb, were at first dismissed by critics as toys or niche markets. Looking for nascent behaviors among early adopters can often uncover valuable new business opportunities.

Enabling Technologies

Wherever new technologies suddenly make a behavior easier, new possibilities are born.

The creation of a new infrastructure often opens up unforeseen ways to make other actions simpler or more rewarding. For example, the Internet was first made possible because of the infrastructure commissioned by the U.S. government during the cold war. Next, enabling technologies such as dial-up modems, followed by high-speed Internet connections, provided access to the web. Finally, HTML, web browsers, and search engines-the application layer-made browsing possible on the World Wide Web. At each successive stage, previous enabling technologies allowed new behaviors and businesses to flourish.

Identifying areas where a new technology makes cycling through the Hooked Model faster, more frequent, or more rewarding provides fertile ground for developing new habit-forming products.

Interface Change

Many companies have found success in driving new habit formation by identifying how changing user interactions can create new routines.

A long history of technology businesses earned their fortunes discovering behavioral secrets made visible because of a change in the interface. Apple and Microsoft succeeded by turning clunky terminals into graphical user interfaces (GUI) accessible by mainstream consumers. Google simplified the search interface as compared with those of ad-heavy, difficult-to-use competitors such as Yahoo! and Lycos. Facebook and Twitter turned new behavioral insights into interfaces that simplified social interactions online. In each case, a new interface made an action easier and uncovered surprising truths about user behaviors.

More recently, Instagram and Pinterest have capitalized on behavioral insights brought about by interface changes. Pinterest's ability to create a rich canvas of images-utilizing what were then cutting-edge interface changes-revealed new insights about the addictive nature of an online catalog. For Instagram, the interface change was cameras integrated into smartphones. Instagram discovered that its low-tech filters made relatively poor-quality smartphone photos look great. Suddenly taking good pictures with your phone was easier, Instagram used its newly discovered insights to recruit an army of rabidly snapping users. With both Pinterest an Instagram, tiny teams generated huge value-not by cracking hard technical challenges, but by solving common interaction problems. Likewise, the fast ascent of mobile devices, including tablets, has spawned a new revolution in interface changes and a new generation of start-up products and services designed around mobile user needs and behaviors.